In the spring of 1927, ambitious cub reporter Calvin Hogue covers a family reunion in the Florida Panhandle.

He learns two Malburn brothers fought on opposing sides during the Civil War, and encourages them to tell their stories.

Before the night is over, Calvin realizes he has a far greater story than a run-of-the-mill family reunion.

Thus begins the first of many sessions with the Malburn brothers. The saga unfolds in their own words with wit, wisdom and sometimes, sadness. Before long the brothers are confronting troubled pasts and conjuring up ghosts laid buried throughout the long post-war years.

Thus begins the first of many sessions with the Malburn brothers. The saga unfolds in their own words with wit, wisdom and sometimes, sadness. Before long the brothers are confronting troubled pasts and conjuring up ghosts laid buried throughout the long post-war years.

Book Excerpt- Chapter One

I FIRST HEARD OF THE Malburn brothers late one Friday afternoon in the spring of nineteen twenty-seven. I was a year out of college and working as a reporter for the St. Andrew Pilot, owned and operated by my uncle, Hawley Wells. It was after five when he summoned me to his office. I walked through the open doorway and stood in front of his desk. The office reeked of stale tobacco. Dust particles swirled in the sunlight streaming through the high windows. A tall floor lamp spilled light across the cluttered desktop and onto the worn hardwood floor.

Uncle Hawley sat hunched over his desk scribbling on a yellow legal pad. As usual, there was a well-chewed Cuban cigar clenched in the corner of his mouth. I bided my time, listening to the scratching of pen against paper and the rhythmic hum of the ceiling fan. I was hesitant to interrupt him. His blustery temper was legendary among the Pilot’s staff. Finally I gathered my courage and cleared my throat.

“You wanted to see me, sir?”

He didn’t answer or look up, just kept writing and mumbling.

“Sir, Mister Dinkins said you wanted to see me?” I glanced at the wall clock behind his desk. There was less than an hour to get home and wash up, pick up my girlfriend and drive to City Hall.

Covering the city commission meeting was a new assignment and I was determined to do an exemplary job. I wanted to prove to my uncle that this cub reporter he’d hired as a favor to his baby sister was capable of handling more than local sports, farm news and garden club socials.

The fact that my girl, Jenny Cotton, worked as a stenographer at the county courthouse didn’t hurt matters either. The way I saw it, with Jenny’s flawless note-taking combined with my writing talent, the esteemed publisher and editor-in-chief would have no choice but to recognize budding genius when he saw it; nepotism be hanged.

Uncle Hawley wrote a few more lines, then laid the pen down and rocked back in his chair. He stared at me for a moment as if I were a perfect stranger, and then took off the ink-stained visor he habitually wore at the office. He wiped a hand across his brow, brushing back imaginary strands of long-lost hair.

“What is it?” he said, the cigar bobbing up and down.

“Mister Dinkins said you wanted to see me.” I was beginning to sound like a stuck Victrola.

“Dinkins, yes.” He glanced down at the yellow pad, then looked up, took the cigar from his mouth and pointed it at me.

“You cover the game this afternoon?”

“Yes, sir, ready for print.”

“Well who the hell won, boy?”

“We did, four to one,” I said, we meaning Uncle Hawley’s alma mater, Harrison High.

He slapped the desktop. “By damn, that’s good news!” Uncle Hawley was a baseball fanatic of some magnitude. He’d once dreamed of playing in the majors, but never made it further than Class D in the now defunct Tri-States League. He grinned and stuck the cigar back in his mouth. “Up by two games in the conference. We beat Holmes County next week, we’re going to State.”

“Yes, sir,” I said, feigning enthusiasm. I found most organized sports boring. Fly fishing was my passion, a pastime largely unheard of here in the warm waters of the Deep South. “If the Hurricanes play like they did today, they’re a cinch.” Uncle Hawley just sat there grinning, so I made a show of pulling my watch from my pocket and examining it. “I need to be at City Hall in a half-hour, sir. You wanted to see me?”

His grin receded into a familiar scowl as he dug through one of the stacks on his desk. “Ah.” He pulled a wrinkled sheet of paper from the pile, stared at it a moment and then looked up. “Got a job for you tomorrow. I was going to put Dinkins on it, but his missus is a week past due already.”

“Tomorrow? But tomorrow is Saturday, sir. I’ve already—”

“Listen up, boy,” he said, waving the paper like a semaphore. “The news waits for no man. Now, you want to be a journalist or were you just wasting your time and your daddy’s hard-earned money at that fancy university?”

My ears burned as I reached for the note. Tomorrow’s matinee at the Ritz was out of the question now, most likely the beach bonfire too. Good thing my girlfriend was the understanding sort. I glanced at the note scrawled in Uncle Hawley’s heavy hand: Malburn brothers, North and South, Econfina, Saturday noon May 28.

I read it again, trying to decipher my assignment. I dreaded asking for more information. When it came to conducting business, Hawley Wells was a man of few words. He expected the hired help to read his mind and carry out his will explicitly.

“Well get going, boy,” Uncle Hawley said. “The commissioners’ll be done with business and halfway to the speakeasy before you even get there. And see Dinkins on your way out,” he called as I hurried through the doorway. “He’ll fill you in.”

It was well past noon Saturday by the time I reached Bennet, a shabby little settlement some twenty miles north of Harrison. The map Harold Dinkins had drawn was easy enough to follow, but I hadn’t counted on being delayed by a road construction gang and a ferry captain who refused to cross Bear Creek until some farmer friend showed up with a truckload of new potatoes.

A mile or so later the road mercifully leveled out and the sandy ruts gave way to washboard clay. Just ahead was Porter’s Bridge, a rickety looking affair fashioned from railroad ties and rough-hewn planking. I stopped the car and got out for a closer inspection. The structure obviously predated Henry Ford, and I wondered if it was safe even for light wagon or buggy traffic. While contemplating whether or not to risk a crossing, I noticed several vehicles parked in a clearing on the far bank. Well, if that many cars and trucks made it safely across, I reasoned, I suppose I could too.

I got back in the roadster, pedaled into first gear and aligned the front tires with the weathered boards. Offering a silent prayer, I eased forward. The bridge vibrated a little but seemed stable enough. Halfway across, a troubling thought occurred to me that maybe those other vehicles had come from that side of the creek.

I felt like Moses at the Red Sea when I finally reached the far bank. I hadn’t dared risk so much as a sidelong glance during the perilous crossing, so I stopped for a minute to view the countryside.

Despite my recent outburst directed at West Florida and its multitudinous shortcomings, I had to concede that Mister Dinkins was right—it was a beautiful setting for a family reunion. The sun-dappled Econfina flowed clear and swift between fern-blanketed limestone banks. Live oaks shaded the picnic area with sprawling moss-draped branches. Through breaks in the trees I saw people sitting around tables and strolling about the grounds.

According to a reunion handbill Mister Dinkins gave me, the Malburn clan had gathered here yearly during the last weekend in May since eighteen sixty-six:

For it was on the 28th of May, 1866, that Daniel, eldest son of James and Clara Malburn, completed his long and arduous journey home from a Yankee prison camp. Word spread quickly throughout the Econfina Valley about the miraculous return of this son long thought dead. Family and friends gathered posthaste to celebrate Daniel’s safe and fortuitous homecoming.

That a family reunion had persevered for sixty years was newsworthy in itself, but what really piqued my curiosity was that Daniel’s younger brother, Elijah, had reportedly fought for the North. My own grandfathers had also found themselves on opposite sides during that most agonizing epic in our nation’s history.

I was eager to learn how the Malburn brothers had conducted themselves when they faced one another at that initial reunion some six decades past. Had the fraternal bond been irreparably breached? How had this brother-against-brother quandary affected their immediate family? Were the Malburns still a house divided, or had all been long-ago forgiven? What of their friends, neighbors, the generations that followed? What had prompted Elijah Malburn, a son of Florida and the South, to join the Union Army in the first place?

From what scant information Mister Dinkins had gathered, there were conflicting stories about what actually occurred. I had so many questions, and only—or so I then thought—a few precious hours to glean the answers from these venerable gentlemen who, though begot from common loins, had once been mortal enemies.

memoir of the Vietnam War, The Proud Bastards,

has been called “As powerful and compelling a

battlefield memoir as any ever written ... a modern

military classic,” and has been in print for most of

the past 20 years.

His work has also appeared in the books: Semper Fi:

His work has also appeared in the books: Semper Fi:

Stories of U.S. Marines from Boot Camp to Battle

(Thunder’s Mouth Press, 2003); Soldier’s Heart:

Survivors’ Views of Combat Trauma (The Sidran

Press, 1995); and Two Score and Ten:

The Third Marine Division History (Turner Publishing, 1992).

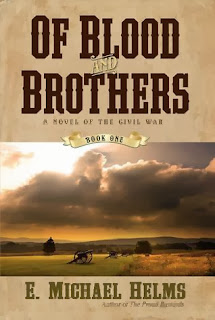

Book One of his two-part historical saga, Of Blood and Brothers, will be released

Septemeber 1, 2013, with Book Two following in March 2014. The first novel of his

Mac McClellan Mystery series, Deadly Catch, is scheduled for a Fall 2013 release.

Helms lives with his wife in the Upstate region of South Carolina in the foothills of

Helms lives with his wife in the Upstate region of South Carolina in the foothills of

the beautiful Blue Ridge Mountains.

**Our Wolves Den is an affiliate for one or more of the products listed or banners seen on throughout this site. If a product review is written I have either received the product free for compensation for writing the post & reviewing the product, or I received compensation in monetary form for the post. Regardless of that fact Our Wolves Den genuinely expresses our OWN opinions 100%. Our Wolves Den is disclosing this information in accordance with the Federal Trade Commission 16 CFR, Part 255 “Guides Concerning the Use of Endorsements and Testimonials in Advertising.” **

1 comment:

I Love Books Like This, Sounds Touching.... Will Have To Read!!

Post a Comment